| Abdul Haq: the Afghan commander who could have led to peace. |

| Source: |

Global Geneva |

By: |

Donatella Lorch |

September 24, 2018 |

On October 26, 2001, Abdul Haq, a renowned Afghan guerrilla, or mujahed, commander was captured by Arab Taliban in the rugged mountains of eastern Afghanistan. Accused of spying, he was hanged and his body riddled with bullets before being dumped on a road. Even now, 17 years later, questions remain as to the exact time and circumstances of his death. And equally crucial, who was involved, including whether nearby U.S. special forces could have rescued him or not. What is known is that Abdul Haq – together with Ahmad Shah Masoud, one of the last remaining leaders resisting the Taliban, who was assassinated by Al-Qaida six weeks earlier on 9 September – had been negotiating for nearly two years with Talib commanders, many of them tired of Pakistani and Al-Qaida supporters’ dominance. By the end of summer, 2001, more than half were believed ready to change sides. While often uncomfortable rivals, both Haq and Massoud, one a Pashtun, the other a Tajik, were two of the country’s most influential and forward-thinking leaders. And yet both were largely ignored by the West. With Massoud’s death, it was up to Abdul Haq to continue the initiative. Former New York Times correspondent, Donatella Lorch, knew Haq well from covering the Soviet war and remained in close touch with him until his final days. She looks back at this extraordinary man who was the last hope to bring about an Afghan solution to this ugly conflict.

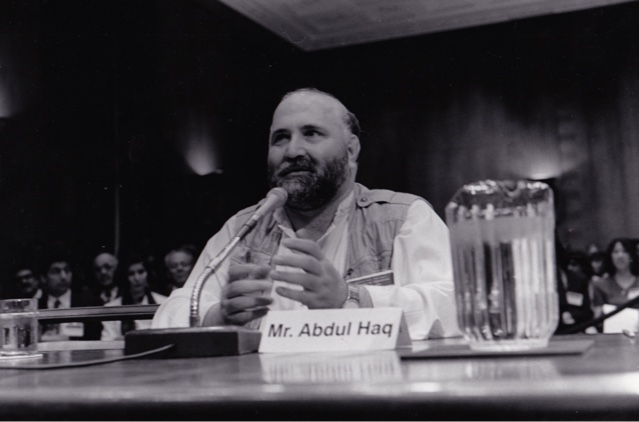

Abdul Haq. Photo: Courtesy Ed Grazda.

FOCUS on Afghanistan: 40 years of war. This is part of a special Global Geneva series on Afghanistan to be published in the November, 2018 – January 2019 print and e-edition.

I had called Abdul Haq from Washington D.C. a few days before he entered Afghanistan. Gone was his habitual jovialness and offbeat sense of humour that had marked our 14-year-friendship. He was frustrated by the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan that had just begun days earlier on 7 October 2001, and his conversation was marked by deep sighs.

“How can I convince Taliban commanders to defect and help create a new, peaceful government when they think America is going to invade?” he said.

I often think of Abdul Haq in the context of the many missed chances for a durable peace in Afghanistan. American bombing, he said over and over, would only tear apart his country. Only an Afghan solution, he believed, would be accepted by Afghans. That October, 2001, Abdul Haq, an unorthodox commander with a strong loyal following, had pleaded with his American contacts to briefly delay the start of the bombing. He needed more time to mobilize Taliban commanders. (Editor’s note: See Lucy Morgan-Edwards’ book, “The Afghan Solution: the inside story of Abdul Haq, the CIA and how Western Hubris Lost Afghanistan”).

Afghanistan’s war has now raged for nigh 40 years, ever since fighting against the communist regime in Kabul first broke out in the summer of 1978. Seventeen of these years have formally involved – and still involve – American soldiers (the U.S. first intervened with support of the mujahideen in mid-1979) but the conflict still grinds on. There is no clear exit. Nor is there any sign of a viable political or military solution despite renewed possibilities of talks between Washington and the Taliban.

Afghanistan: A litany of failed initiatives

Afghanistan is an unrelenting string of gut wrenching tragedies, of civilian and military lives lost, of misdirected, shortsighted, dysfunctional and failed international policies. Billions of dollars of military and international aid have fed a fragile government mired in corruption. Like his country, Abdul Haq’s narrative varies depending on who tells it: the U.S. military and its allies, the CIA, the Pakistan military intelligence service (ISI), the journalists…

But then, I think that Abdul Haq, even when he was maligned, understood the value of being an enigma. Unlike most other mujahed leaders, he knew how to fit into two worlds: the one of conservative tribal Afghanistan and the political realms of the western capitals.

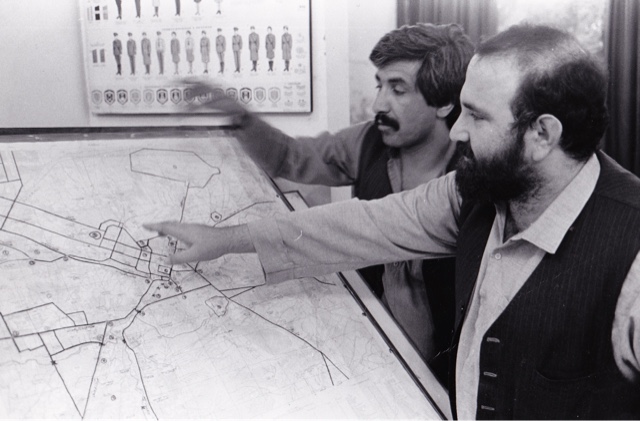

Donatella Lorch (R) with mujahed fighter inside eastern Afghanistan. (Photo: Lorch)

I was 26 when I met Abdul Haq. He was 30. This was in 1988, by chance. Although over time, I have realized that nothing in Peshawar (the Pakistani border city with Afghanistan that served as headquarters for the main Afghan political resistance groups) really happened by chance. I’d first seen him on one of those heroic-looking public relations posters printed by the mujahideen, a romantic headshot of a tanned, bearded young man with a headful of curly windblown brown hair framed against an Afghan mountain. The man I met was older. He’d lost his curls, his hair was fast thinning and he’d packed on weight.

A maverick of independent thinking – and actions

Born Humayun Arsala, his nom de guerre became Abdul Haq (servant of justice) but his men all referred to him reverentially as Haji Sahib (Haji denoting that he had been on the Haj or pilgrimage to Mecca). Abdul Haq was a Pashtun, born to a wealthy landed family in eastern Afghanistan that had close ties to the then Afghan King Zahir Shah exiled in Rome.

He had a resumé as a maverick and as a strategist. As a teenager, Abdul Haq participated in four attempts to overthrow the Soviet-backed government of Mohammed Daoud. At 17, he was arrested and condemned to death. His family organized his escape by bribing the prison officials. By the time he was 21, Abdul Haq already had built a reputation as a talented commander by attacking the capital Kabul and running an underground network of spies and informers.

Abdul Haq, an exceptional urban guerrilla strategist. (Photo: Courtesy Ed Grazda)

The year before I met him, Abdul Haq had walked on a landmine and lost the front half of his right foot. By then, he had already been wounded more than a dozen times, but the loss of mobility forced him out of the field, directing most of his operations from his Peshawar compound. When I first saw him, he was sitting cross-legged on a dark red pillow that ran the length of the wall in his compound. He was sipping green tea, rubbing the stump of his foot, and holding meetings with a room-full of turbaned, long-bearded men. He was a paradoxical man, which often left me baffled. He spoke English (peppered at times with drunken sailor vocabulary learned from a Dutch journalist) in a short, declaratory style. He was candid at times to the point of rudeness.

The United States: a dinosaur that steps on everyone

He claimed to be uneducated, but then he’d delve into analyses of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty, and the problems facing American farmers. A tradition-bound Muslim, he acquiesced to an arranged marriage but he talked of a female president for Afghanistan. He had visited the U.S. several times and had met President Ronald Reagan. In late 1987, he had gone to a Pittsburgh hospital to have his maimed foot operated and in June 1989, he would go to New York to address the United Nations. His analyses were blunt and uncannily real.

“The U.S. is like a dinosaur,” he told me over tea one afternoon. “It’s a huge animal with a little brain that steps on everyone indiscriminately.”

Abdul Haq liked to do everything with flair. He was a bear of a man who hurled himself into chairs, square and burly and balding with thick paw-like hands and a big round belly. French diplomats and relief agencies called him L’Ours, the bear. Our meetings were often over sweets and lengthy meals where he downed gallons of green tea and what he referred to as his one western vice: diet coke. He had a voracious appetite both for food and life.

Hollywood ‘Haq’: An outspoken critic of the CIA and ISI

Donatella Lorch reporting for the New York Times during the late 1980s in eastern Afghanistan with Mohammed Shuaib, an Afghan who worked as interpreter and guide with many journalists. (Photo: Lorch)

In my two years based in Peshawar covering the resistance side of the war during the nearly decade-long Red Army occupation of Afghanistan, I travelled with his men to the outskirts of Kabul as they rocketed the capital. A few months later, in 1989, he had me smuggled into Kabul disguised as an Afghan woman to write about his underground network. I also witnessed meetings of major commanders in rebel-controlled areas. Abdul Haq was blunt and daring and gave me the impression of moving into the unsettling unknown with great pleasure. His men both in and out of his presence worshipped him. Though he had been one of the CIA’s main contacts in the early war years, he later became a vocal critic of both the Pakistani ISI and the CIA who nicknamed him “Hollywood Haq”.

After the fall of Kabul in 1992, he briefly joined the new government but, sickened by the bloody and relentless inter-ethnic conflict, he moved to Dubai. In 1999 he joined with Ahmed Shah Massoud, the well-known Tajik commander, to try and unite the country’s many ethnic groups against the Taliban. This, both of them believed, was the only viable long-term path to peace. There could be only one solution: an Afghan one. Still, he never doubted the viciousness of his own opponents.

“We may not know how to make computer chips,” he told me. “But we do know how to do one thing well. We know how to kill.”

The Afghan government: a failed and corrupt leadership

For almost two decades, my work life was linked to the Afghan conflict. Afghanistan was my first war. In the 1980s, I frequently interviewed Hamid Karzai, the country’s future president, though back then he was an immaculately-dressed mujahed spokesperson without any significant following. Many in the original pantheon of soullessly vicious Afghan warlords are now even more powerful, cruel, corrupt and more prominent in the present government.

Much of this had been made possible by the fact that they had been co-opted early on by the CIA, who operated primarily through ISI, who favoured their ‘own’ mujahideen. The Americans provided the guerrillas with planeloads of millions of dollars in cash, weapons and ammunition. To avoid breaking U.S. law, ammunition and weapons had to be delivered (often air-dropped) in separate planes.

The bombing campaign in Afghanistan, which began in October, 2001, was called Operation Enduring Freedom. It was meant ‘to disrupt the use of Afghanistan as a terrorist base of operations and to attack the military capability of the Taliban regime.’ Today the Taliban and their Al-Qaida allies, including IS, are stronger than ever. The American military is bogged down and extremism is spreading far beyond its borders. The only part of the campaign slogan that truly endures is an unrelenting destruction of Afghan lives, livelihoods and culture.

Unlike Abdul Haq, many of the Afghan mujahedpoliticians dating back to the 1980s became, after the overthrow of the communist regime – and especially after 9/11 – deeply corrupt, lavishly wealthy and powerful.

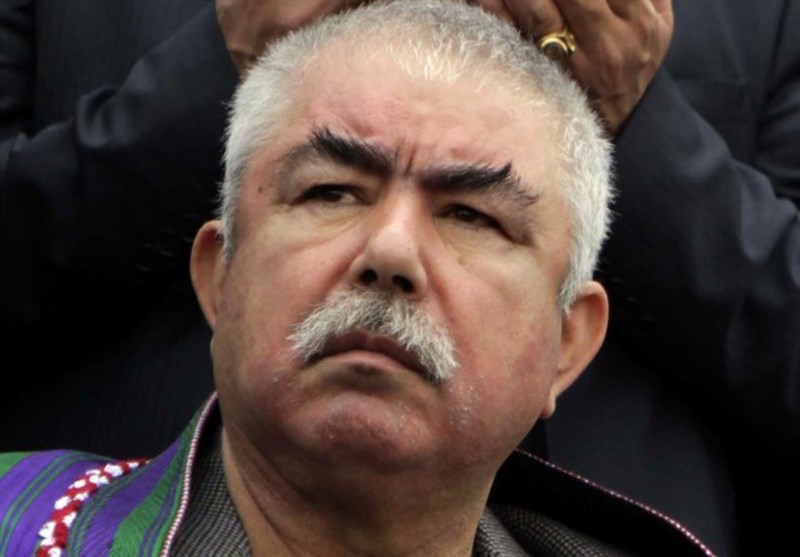

Abdul Dostom: Facing allegations of crimes against humanity

Dostum: A veritable monster now back in office

One of them, General Abdul Rashid Dostum, an ethnic Uzbek warlord and now the country’s first vice president, is an example of the monsters created by the belief that bombing Afghanistan would defang the Taliban and cripple Islamic extremism. In 1992, in a battle for control of a newly liberated Kabul, I saw Dostum’s men rocket and flatten entire neighborhoods, killing civilians indiscriminately. I met Dostum face to face in 2002, in northern Afghanistan, when he was accused of having suffocated hundreds of Talib prisoners held in containers.

Most recently, invited by Afghanistan’s current president Ashraf Ghani, who had once called him “a known killer”, Dostum returned to Kabul after a year of self-imposed exile in Turkey. He still faces charges of rape and kidnapping, brutality, human rights abuses and the killing of his first wife. Yet in Kabul, he received a royal welcome from both his supporters and the government.

Abdul Haq’s last venture: A decision not in vain?

Abdul Haq was a pragmatist with a long-term vision. But he didn’t want the Pakistanis or the Americans to control him. So in death as in life, they belittled his role. For a while, even I was uncertain. Did he really know Talib commanders? It is easy to get muddled in the maze of conspiracy theories spread by all sides.

Recently I found a clue in the footnotes of a book about Afghanistan that answered many of my doubts. Abdul Haq, it merely stated, had the backing of Khan Mir, a powerful Talib commander near Jalalabad with over 800 men. I was convinced this was the Khan Mir that I knew.

Khan Mir was the charismatic commander who had taken me many times inside Afghanistan. We had come under rocket attack together and escaped by hiking for days in snow and rain. Throughout a moonless December night, I had walked in his boot prints down a mined mountainside. I knew his wife and his children and his brothers.

Back in 1988, Khan Mir was Abdul Haq’s right-hand man. And Khan Mir worshipped Abdul Haq, the way Khan Mir’s own men followed him. He believed in Abdul Haq and what he stood for.

Maybe it hadn’t been all in vain. Crossing the border that night in 2001 was a gamble but it was not a fool’s trip. Since then, there are clear indications that many commanders – on learning that key brethren, such as Khan Mir, were also involved – were prepared to switch sides. And yet, the last thing that Islamabad wanted was an independent-minded new leadership promoting the possibility of real – and Afghan-led – peace.

Furthermore, in the belligerent atmosphere of post-9/11, neither Washington and London arrogance were really interested in an Afghan solution. Confusing the Taliban with Al-Qaida, the Afghans had to be punished. And besides, a political initiative could take months, even years. The military option, the Bush administration believed, offered the quickest ‘solution’.

And yet both Abdul Haq and Massoud (who met with US officials in Paris in April 2001) had warned the West that a military intervention would only provoke more war. The end result is that – looking back today – little or nothing has been achieved. And a huge opportunity was lost.

Donatella Lorch, a former New York Times and NBC correspondent, has written previously for Global Geneva. She is currently based in Turkey. |